Epistemic logic and the problem of common knowledge

With the two generals, Cheryl's birthday, hidden surprises, blue-eyed islanders, pirate treasure division, philosopher's ruling council, coordination paradox, Fitch's paradox, Cheryl's rational gifts

Three logicians walk into the Logic Bar.

Waiter Do you all want beer?

First logician I don't know.

Second logician I don't know.

Third logician Yes.

Hilarious! ... did you get it?

To explain a joke is seldom funny, of course, but kindly humor me. The joke turns on epistemic logic, the logic of knowledge, for the waiter had asked whether they all want beer, you see, and so the logicians were answering not only for themselves but also regarding what they knew about whether the others wanted beer. Because the first logician said, "I don't know," it must have been that she wanted beer, but didn't know if everyone wanted beer. If she herself had not wanted beer, then she would have said simply "no," since she would have known that they didn't all want beer; but it would have been wrong for her to say "yes" merely because she herself wanted beer, not knowing about the others, since the question is whether they all want beer. Similarly, we can tell that the second logician must want beer, since otherwise he would have said "no," but he doesn't know whether the third logician also wants beer. Finally, the third logician, reasoning just as we have, knows that the other two want beer, and since evidently he also wants beer he says "Yes," since he now knows they all want beer.

In this chapter we shall have a series of fun epistemic logic puzzles, many of which will lead us to further serious issues in epistemic logic.

The two-generals problem

Let us begin with a classic problem in epistemic logic known as the two-generals problem. Two red generals and their armies are situated on mountains overlooking a valley between them.

They want to coordinate a joint attack on the blue army in the valley, but they are separated by the terrain and they must coordinate the precise details and timing of the attack in advance. If both attack simultaneously, they will succeed; but if either should delay or attack alone, they will both fail. Meanwhile, the communication channels are difficult and unreliable.

The first red general dispatches a messenger through the dangerous blue valley:

We attack at dawn; agreed?

The message gets through! The second red general replies,

Yes, at dawn! Please confirm.

He needs confirmation, you see, since otherwise he might think that the first general would think that the original message had not made it. So the first general confirms,

Received your message! Ready to go at dawn...provided we know you get this message.

This confirmation also needs confirmation, since otherwise, the first general wouldn't know that the second general had received the necessary confirmation, and he would therefore call off the plan. So the second red general verifies that indeed he received it.

Got it! We're definitely on, once we know you have received this.

And so on, back and forth. The brave messengers make it through each time against the odds. At each stage of the process, however, the generals need confirmation that their message was received, in order that they would know that the other general will undertake the plan, since otherwise, they would have grounds for thinking that they would be attacking alone, a dangerous possibility.

How much confirmation suffices? Can the two generals ever become fully confident in the coordination of their joint plan?

Interlude

Let me argue that in fact the two generals can never become completely confident, no matter how many messages they send. Clearly, the first message needs confirmation, in order for them to be completely confident, since otherwise the first general could not know that the second general even knows of the plan in the first place. And it is also clear that the reply to this message needs its own confirmation, since otherwise the second general would worry that his reply hadn't made it through, and in this case he would conclude that the first general would have no reason to think his original message was ever received and therefore abandon the plan.

Similarly, if neither general is confident after sending n messages, then they cannot become confident after sending n + 1 messages. The reason is that since the last message will not be confirmed, then the confidence should arrive whether or not this final message makes it through. But in this case, it needn't have been sent at all—the effects on communication would be the same—and so they should have already been confident in the plan with only n messages, contrary to our assumption. Thus, by induction, no finite number of message will suffice.

A slightly different way to argue is like this. Suppose toward contradiction that some finite number of messages suffice for the generals to be confident that they have reached agreement on the joint attack plan. Let n be the smallest number of messages that suffice. In particular, the generals should become perfectly confident in their agreement upon exchanging those n messages. But in this case, since the final message will get no confirmation of receipt, the generals should become confident whether or not that last message actually makes it through. But in this case, the last message needn't be sent at all, since the communication effect of a message that gets lost is the same as one that is not sent in the first place. Thus, n - 1 messages actually suffice for the generals to achieve complete confidence. This is a contradiction to the minimality definition of n.

The surprising conclusion is that no finite number of messages exchanged back-and-forth can ensure that the generals have the information that is required for them to be fully confident in the joint attack plan.

Mutual knowledge versus common knowledge

Suppose that we all know that there is a dangerous crocodile inside the large box at the front of the lecture hall. None of us would elect to open the box, since this would release the crocodile and cause chaos.

We have mutual knowledge—we all know it individually—that there is a crocodile in the box. Knowing this, however, is not quite the same as knowing that all the others also know this. We would surely behave differently if we didn't know that everyone else knew about the crocodile; we might be anxious, for example, that someone would open the box out of curiosity, without expecting or realizing the danger.

A prudent person would therefore likely announce for all to hear that there is a dangerous crocodile in the box. The aim of such a public announcement would be to create a state of common knowledge about the danger, a state where not only do we all know that there is a crocodile in the box, but we also know that we all know it, and we all know that we all know that we all know it and so on.

The two generals similarly are striving (but failing) to create a state of common knowledge about their plan. After the first message gets through, they both know of the plan, but that isn't enough, since the first general needs to know that the second general knows the plan. And that isn't enough since the second general needs to know that the first general knows that the second general knows the plan. What we had argued in effect is that no finite amount of iterating "I know that you know that..." will suffice for common knowledge.

Let us try to give a somewhat more formal account. We say that a collection of individuals are in a state of common knowledge of a proposition p, if every individual knows p, and also every individual knows that every individual knows p, and every individual knows that every individual knows that every individual knows p, and so on for every finite iteration. Let us write □a p to indicate that individual a knows p. This notation views knowledge as a kind of necessity, in light of many features of knowledge that obey some of the logical principles holding for other concepts of necessity.

In this notation, to say that every individual knows p is to assert:

To say that every individual knows that every individual knows p is to assert:

And so on. The state of common knowledge is reached when we have all the finite iterations:

Thus the state of common knowledge is described formally by this infinite scheme of assertions.

The two-parents problem

Consider a contemporary variation of the two generals problem, which I had experienced myself. When my kids were younger, my wife usually picked up our daughter Hypatia at her school, while I would pick up our son Horatio at his school, a different school in a different neighborhood. One day, because of an errand, it was convenient to swap tasks. So I emailed my wife,

I'll pick up Hypatia today; you get Horatio. Please confirm; otherwise it is as usual.

She texted back,

Let's do it! Let me know, so I know we're on.

So I left her a voicemail message,

OK, we're on for the swap...as long as I know you get this message.

And she direct-messaged me back,

Got the message. We're on! But let me know that you get this message so I can count on you.

And so on.

Just as with the two generals, it seemed that at no stage of the conversation could we know for certain that the other person had all the necessary information to count on the other person making the swap. One cannot count on another person actually reading an email or text, and sending such a message may often be as uncertain as dispatching a horse-mounted messenger through a dangerous enemy valley.

Clearly the first message needed confirmation, and the reply needed its own confirmation, for otherwise she couldn't have known that I got the confirmation; and then that reply needed to be confirmed, and so on endlessly, just as before.

In the end, despite all our messages, we both did the logical thing: we abandoned the swap idea and just picked up the usual child at the usual school.

Internet communication protocols

These problems might seem silly or artificial, but let me try to convince you that they are not. The reason is that essentially the same issues arise in the design of internet communication protocols. When you click on a link on a web page, for example, your computer needs to communicate with other computers in such a way that they can coordinate together to send and receive the information. When will a video stream be sent? How will a financial transaction be completed? Your computer needs to be ready to receive information at the right time when it is sent by the other computer, and the nature of this communication is essentially identical in important respects to the issues of the two-generals problem. The two-generals impossibility argument shows that there is no protocol that solves the problem perfectly, and one must accept protocols that compromise and operate with incomplete confidence. And sometimes, as we are all aware, the joint operations fail.

Do public announcements lead to common knowledge?

Earlier we had mentioned the possibility of achieving common knowledge with a public announcement. When someone announces publicly for all to hear, "there is a dangerous crocodile in the box," then we all seem to know not only that fact, but also the fact that everyone knows it, and the fact that everyone knows that everyone knows it, and so on. Public announcements are often presented by philosophers as a means to achieve the state of common knowledge.

But is this right? In practice, of course, actual public announcements often do not have this character. A scratchy public announcement on the noisy subway might be understood by fewer than half of the passengers; but even if it is understood by all, they might not come to know that everyone knows the information, since perhaps some of them might reasonably believe that others may not have understand it.

But even with a crystal clear public announcement, I claim, we might reasonably harbor some doubt about whether everyone was paying attention, and this would prevent us from all knowing that everyone knows. Even if nobody happened to have such doubts, in order to achieve common knowledge we would all need to know that nobody had such doubts—otherwise we would not know that everyone knows that everyone knows the information. But do we actually get this information from a public announcement? For me to know that everyone knows that everyone knows the information, I would have to know that nobody noticed something strange that might have given them reason to think that a particular person might not have been paying attention. Perhaps for all I know someone might have noticed someone with eyes closed during the announcement and suspected that they might have missed it—I didn't see anyone with eyes closed, but do I truly know that nobody else saw someone like that? I don't think I do. Even if I paid very close attention, and indeed even if everyone paid very close attention, would I truly know that everyone paid enough attention to know that everyone knew that everyone knew the information? I don't think so. And the situation is even more uncertain when it comes to knowing that everyone knows that everyone knows that everyone knows the information.

To my way of thinking, a mere public announcement, even a perfectly clear public announcement that was obviously heard by everyone, does not generally achieve these higher levels of iterated knowledge of knowledge as in our formal account of common knowledge. For this reason, I don't believe that common knowledge can be obtained so cheaply as a public address system. To my way of thinking, public announcements do not generally achieve full common knowledge.

I claim further that there is genuine difficulty of achieving common knowledge even with two people talking to each other directly. Imagine that my wife and I were talking to each other on the phone, instead of exchanging messages, or perhaps even talking in person face-to-face. Doesn't the same difficulty arise with our coordination? I would propose to swap the child-pickup duties, and she would agree, but she would need to know that I understood her agreement, so I would need to confirm that somehow, perhaps by nodding, and I would need to know that she noticed that, and so on ad infinitum. Do we actually achieve this infinitely-iterated knowledge of confirmation? I don't think so. How is coordination communication ever possible? Can the two generals achieve the necessary joint coordination even if they are speaking face-to-face?

One answer, of course, is that we don't ever actually achieve the perfect state of common knowledge; rather, we make do with partial knowledge. We might confirm back and forth only, or perhaps confirm several more times back and forth in critical instances, and then simply proceed with the resulting approximation to common knowledge. In most instances, this amount of knowledge suffices for our purposes.

Cheryl's birthday problem

A few years ago, this logic puzzle from the Singapore Math Olympiad went viral on the internet, stumping millions of people all over the world. Can we solve it? Here is the problem:

Albert and Bernard are friends with Cheryl, and they want to know when her birthday is. Cheryl provides a list of 10 possible dates:

May 15 June 17 July 14 August 14

May 16 June 18 July 16 August 15

May 19 August 17

Cheryl then tells Albert and Bernard separately the month and the day of her birthday, respectively. Discussion ensues.

Albert I don't know when Cheryl's birthday is, but I know that Bernard also does not know.

Bernard At first I didn't know Cheryl's birthday, but now I know.

Albert Then I also know when Cheryl's birthday is.

When is Cheryl's birthday? Please try to solve the problem on your own, before continuing. Tens of thousands of people on the internet have done so, and I am confident that with careful thought, you also can solve the problem. Give it a good amount of time and thought; the problem is worthwhile.

Interlude

Welcome back. Did you solve it?

Let me explain how I think about it. At first, Albert has only the month and Bernard has only the day, and to make an implicit point explicit: let us assume that they know this in the state of common knowledge. Albert begins by saying that he doesn't know when Cheryl's birthday is. Well, of course he doesn't know, since all he knows at first is the month, and each of the months has several possible days.

But then Albert says something interesting, namely, that he also knows that Bernard doesn't know the birthday either. Now, looking at the chart of possible birthdays, the only way Bernard could know the exact birthday is if the day number was either 18 or 19, since in each of those cases, there is only one birthday on the list with that number, whereas for each of the other numbers, there are multiple birthdays with that number. So, when Albert says that he knows that Bernard doesn't know, it must be that the information that Albert has is incompatible with Bernard having either 18 or 19. Thus, Albert must not have May or June. So Albert has either July or August.

Bernard says that at first he didn't know Cheryl's birthday, but now he knows. Thus, the date is not 14, since otherwise Bernard wouldn't know the birthday at this point, since that day number occurs in both July and August. So it must be either July 16, August 15 or August 17, and Bernard knows because he must have one of those numbers. Finally, Albert says that he now knows Cheryl's birthday. This implies that Albert cannot have August, since if he did, he wouldn't have known whether it was August 15 or August 17. So Albert has July, and therefore the birthday must be July 16, which solves the puzzle.

A variation on Cheryl's birthday

Let us consider a variation of the puzzle that I have devised. The following weekend, Albert, Bernard and Cheryl get together again for more conversation. Cheryl privately gives Albert and Bernard each a positive integer, amongst 1, 2, 3, and so on.

Cheryl I gave you each a different positive integer. Whose is larger?

Albert I don't know.

Bernard I don't know either.

Albert I still don't know whose number is larger.

Bernard Alas, I remain in ignorance.

Albert Ah, now that you say that, suddenly I know whose number is larger!

Bernard Really? In that case, I know both numbers!

Albert And now I also know both numbers.

What numbers did she give them?

Interlude

Let us solve the puzzle together. Albert and Bernard have different positive integers, amongst 1, 2, 3 and so on, possibly very large. And furthermore, they both know that information and they know that the other person knows it and so on, since it was announced clearly enough by Cheryl. When Albert begins by saying that he doesn't know who has the larger number, it must be that he doesn't have 1, since if he had 1, then he would have known that Bernard's number would have been larger. But really that is all that we may deduce about his number, since if he had had any number other than 1, he couldn't know whether Bernard's number was smaller or larger.

When Bernard replies that he doesn't know either, then it follows similarly that Bernard doesn't have 1, but also that he doesn't have 2, since he already knows that Albert doesn't have 1.

Albert says next that he still doesn't know whose number is larger, which means that Albert must not have 2 or 3, since in those cases he would have known. And since after this Bernard announces that he remains in ignorance, Bernard must not have 3 or 4.

Now, suddenly, Albert announces that he knows who has the larger number. How could he know that? Well, he must have either 4 or 5, because if he did, then he would know that Bernard's number is larger, since Bernard has been excluded from 1, 2, 3 and 4 already; but if he had a number larger than 5, then he couldn't know that Bernard didn't have 5, and so he wouldn't know who had the larger number. So Albert has either 4 or 5, but we don't know which yet.

Meanwhile, finally, Bernard says that he now knows both numbers. For Bernard to know that, he must have one of the numbers 4 or 5, in order to exclude it as a possibility for Albert. But we've already argued Bernard cannot have 4, and so he must have 5. Thus, Albert has 4 and Bernard has 5. When Albert says that he also knows both numbers, it is because he could reason just as we just did.

Reciprocal variation

Suppose that Alice and Bob are each given a different fraction, of the form 1/n, where n is a positive integer, and it is commonly known to them that they each know only their own number and that it is different from the other one. The following conversation ensues.

JDH I privately gave you each a different rational number of the form 1/n. Who has the larger number?

Alice I don't know.

Bob I don't know either.

Alice I still don't know.

Bob Suddenly, now I know who has the larger number.

Alice In that case, I know both numbers.

What numbers were they given?

When Alice says she doesn't know, in her first remark, the meaning is exactly that she doesn't have 1/1, since that is only way she could have known who had the larger number. When Bob replies after this that he doesn't know, then it must be that he also doesn't have 1/1, but also that he doesn't have 1/2, since in either of these cases he would know that he had the largest number, but with any other number, he couldn't be sure. Alice replies to this that she still doesn't know, and the content of this remark is that Alice has neither 1/2 nor 1/3, since in either of these cases, and only in these cases, she would have known who has the larger number. Bob replies that suddenly, he now knows who has the larger number. The only way this could happen is if he had either 1/3 or 1/4, since in either case he would have the larger number, but we can't be sure yet which one he has. When Alice says that now she knows both numbers, however, then it must be because the information that she has allows her to deduce between the two possibilities for Bob. If she had 1/5 or smaller, she wouldn't be able to distinguish the two possibilities for Bob. So she must have 1/4 (as 1/3 is already forbidden to her by our earlier analysis). So Alice has 1/4 and Bob has 1/3.

Hidden prize problems

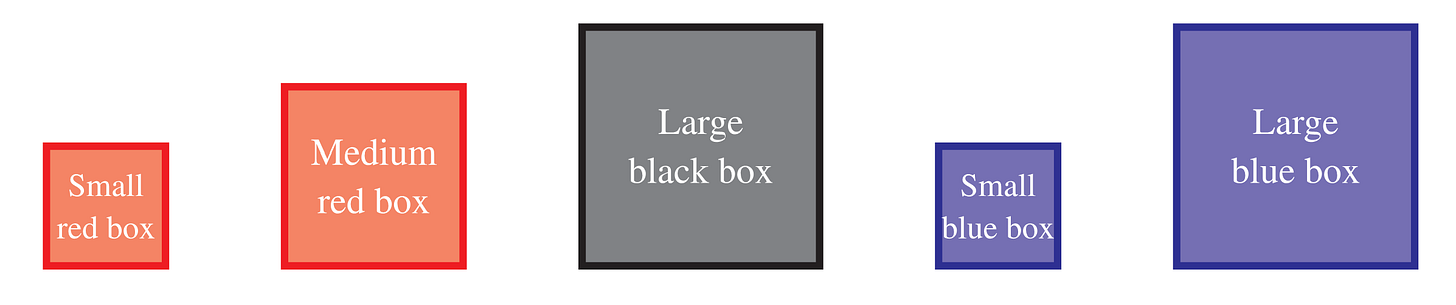

The gift box

Alice has invited her friends Caroline and Susan to her home, and she has placed several boxes on the table before them. They are all very logical.

Alice tells her friends that she has placed a gift into one of the boxes, and she has privately told Caroline the color of the box and Susan the size of the box, and they both have common knowledge of this. The following conversation ensues.

Caroline I don't know which box contains the gift, and I also know that Susan doesn't know.

Susan I already knew before you spoke that you didn't know which box contains the gift.

Caroline Ah, now that you say that, it suddenly occurs to me which box must contain the gift.

Which box contains the gift? After the conversation, does Susan also know which box contains the gift? If so, who came to the knowledge first, Caroline or Susan?

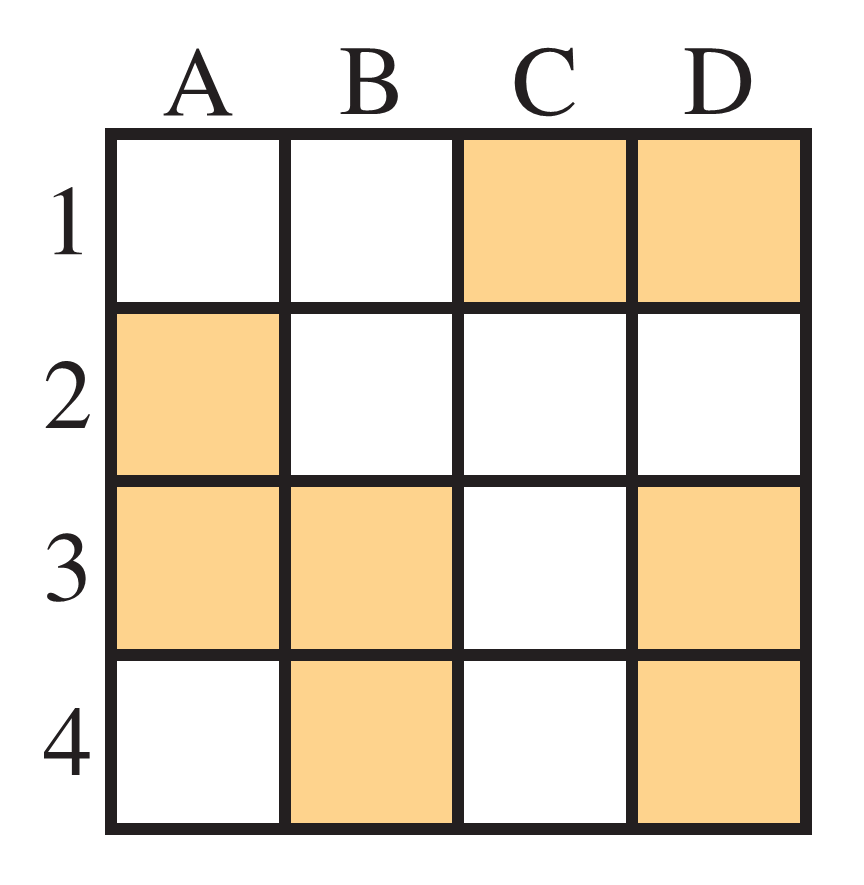

Hidden surprise under a tile

Jonathan has invited his friends Roland and Christopher, both very logical, to his home. He tells them that he has hidden a surprise under one of the orange squares.

Jonathan has privately told Roland the row number of the surprise and Christopher is told the column letter, and this situation is commonly known. The following conversation ensues.

Roland I don't know where the surprise is, but I also know that Christopher doesn't know.

Christopher Yes, indeed, at first I didn't know the location of the surprise. But now I know where it is.

Roland In that case, I now also know where it must be.

Where is the surprise?

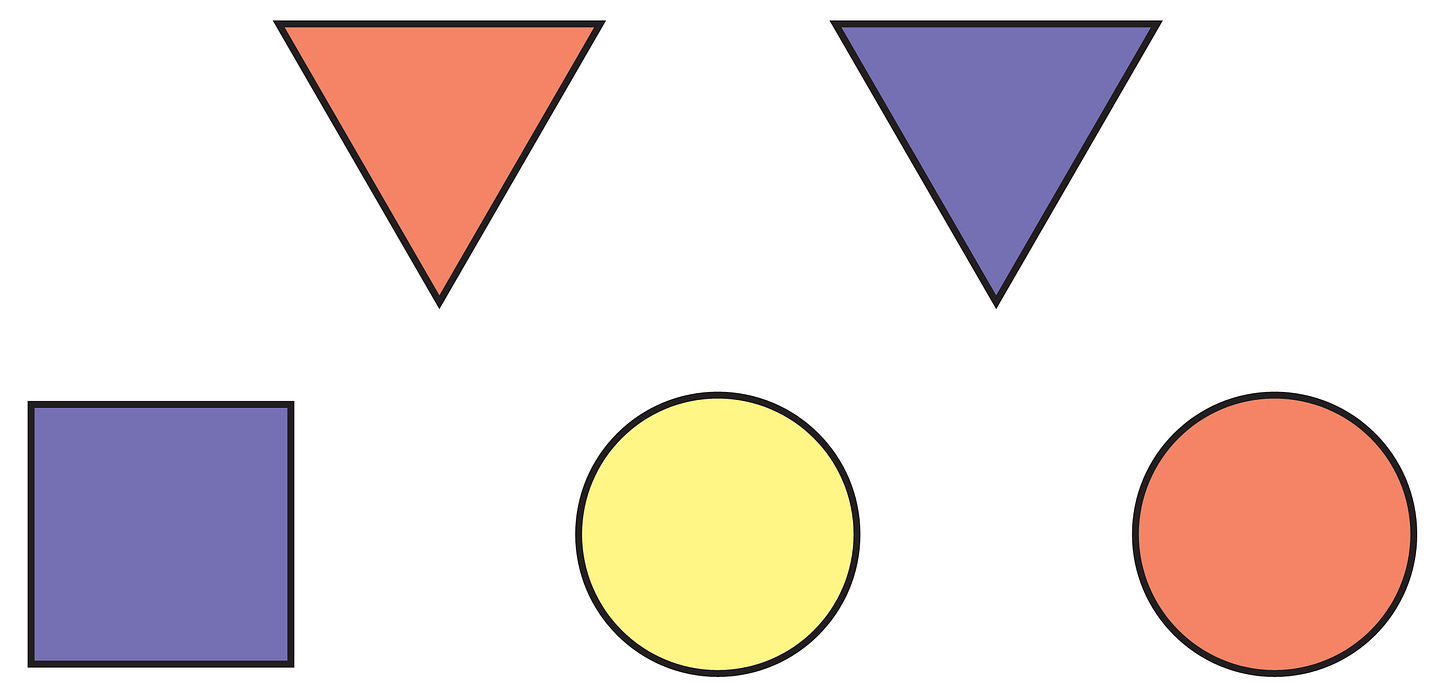

More hidden surprises

At a party for our perfectly logical philosophy friends Sheila and Colin, a surprise has been hidden under one of these colored tiles:

Each friend is privately told a piece of information about where the surprise is.

Sheila knows the shape of the tile.

Colin knows the color of the tile.

It is commonly known by all that this and no other information is given.

The following conversation begins.

Host Does either of you know where the surprise is?

... Awkward long silence...

Host Do you know now?

... More awkward silence...

Sheila, Colin (simultaneously) Now I know where it is!

Where is the surprise?

Interlude

If it were the yellow circle, Colin would have known right away. So it is not yellow. Similarly, if it were square, then Sheila would have known right away. So it isn't square. After the first silence, then, if it were the red circle, then Sheila would have known, since only one circle left; and if it were the blue triangle, then Colin would have known, the only blue shape left. So after the second silence, both of them deduce, as we have, that it must be the red triangle. The reader is invited to consider several followup questions in the Questions for Further Thought.

See also the account of this puzzle on YouTube, currently with over 6 million views:

The blue-eyed islanders

A remote island has one hundred perfectly logical inhabitants, with excellent eyesight, and they all know this. Furthermore, they all happen to have vivid deep blue eyes.

However, it is part of their cultural practice never to discuss eye color, and if any of them should come to know they have blue eyes, then they must leave the island the next dawn with a flashy display visible to all inhabitants. For this reason, there are no mirrors or cameras on the island and they never view their own reflections. And indeed, none of the islanders knows his or her own eye color.

One day a trusted visitor arrives at the island, and has an enjoyable stay with them. Departing at the end of her visit, in front of the entire community assembled for her departure, she remarks, "At least one of you has blue eyes." Exactly one hundred days later, it turns out, all the islanders make a big flashy display at dawn and everyone leaves the island.

Why? Can you explain how the islanders each came to know that they had blue eyes on that day?

Interlude

Let's solve the puzzle together. It will be illuminating to begin with some easier instances. Consider first the trivial case where there is only one blue-eyed inhabitant, rather than one hundred. When the trusted visitor says, "at least one of you has blue eyes," the sole islander naturally deduces that it must be himself, and so he performs the flashy departure display at dawn the next morning and exiles himself.

Next, consider the case of just two islanders, each with blue eyes. Each of them knows that the other has blue eyes, of course, but each is initially unsure of his own eye color. When the visitor remarks that at least one of them has blue eyes, then each of them undertakes the following line of thought: If I don't have blue eyes, then the other islander will know that, and since he also just learned that one of us has blue eyes, he will deduce that he has blue eyes himself; in that case, at the next dawn he will make a flashy display. When no display occurs the next day, then both islanders will continue their reasoning: since the other islander didn't make a flashy exile display, it must be because I myself have blue eyes, and he was wondering whether I would have made the flashy display. Thus, having deduced their own blue eye colors, the two islanders will both make a flashy display at the dawn of the second day and depart the island.

In the case of three islanders, each of them will consider the possibility that they do not have blue eyes, and since the other two islander do have blue eyes, in this case each would expect the other two to go through the reasoning process of the two-islander case. Specifically, in this case each of the others would see one other islander with blue eyes and wonder whether they themselves also have blue eyes; if not, then the other islander would have made the flashy display on the first dawn, but this doesn't happen (since each actually sees two people with blue eyes), and so they would both know that they have blue eyes and make the flashy display on the second dawn. But that doesn't happen (since all three are waiting to observe this behavior in the other two), and so now they all know that they all have blue eyes, and so the flashy displays come on the third dawn after the announcement.

And so on for more islanders. The general claim, which I shall argue by induction, is that if there are n blue-eyed islanders and possibly some other non-blue-eyed islanders, then they will all come to know this by the dawn of the nth day after the announcement, making the flashy display and departing on the nth day. We have argued already that this is true for n = 1. Suppose this is true for n, and consider now the case of n + 1 blue-eyed islanders. Each of them considers that perhaps they don't have blue eyes, in which case there would be n blue-eyed islanders, and so they are all expecting possibly to see all the others make the flashy display and depart on the nth day. But when that doesn't happen (since they are all waiting to observe if the others do it), each islander deduces that he must have blue eyes after all. Since each of the n + 1 blue-eyed islanders go through this reasoning, independently deducing that they have blue eyes, they all make the flashy display and depart at dawn of day n + 1. By induction, therefore, the claim is proved for all n, and in particular, for n = 100 as in the puzzle. Thus, we have solved the puzzle.

A subtle conundrum

Notice that the statement that the visitor makes, "at least one of you has blue eyes," was something that each of the islanders already knows at that time. But how can it be that making a public statement about something that everyone already knows sets into motion the elaborate reasoning process leading to their regrettable exile?

The answer is that it isn't just the fact of that statement that matters for the reasoning process of the islanders, but rather, the fact that each islander knows that the others also know the statement, and that they know that everyone knows that everyone knows it. And so on, iterated one hundred times. In short, what mattered is that the islanders are in a state of common knowledge about the fact that at least one of them had blue eyes.

The pirate-treasure division problem

The pirate ship with a crew of fearsome, perfectly logical pirates and a treasure of one hundred gold coins to be divided amongst them. How shall they do it?

The pirates have long agreed upon the pirate-treasure division procedure: The pirates are linearly ordered by rank, with the Captain, the first Lieutenant, the second Lieutenant and so on down the line; but let us simply refer to them as pirate one, pirate two, pirate three and so on. Pirate nine is swabbing the decks in preparation.

For the division procedure, all the pirates assemble on deck, and the lowest-ranking pirate mounts the plank. Facing the other pirates, he proposes a particular division of the gold, with so-and-so many gold pieces to the captain, so-and-so many pieces to pirate two and so on. The pirates then vote on the plan, including the pirate on the plank, and if a strict majority of the pirates approve of the plan, then it is adopted and that is how the gold is divided. But if the pirate's plan is not approved by a pirate majority, then regrettably he must walk the plank into the sea (and his death) and the procedure continues with the next-lowest ranking pirate, who of course is now the lowest-ranking pirate.

Suppose that you are pirate ten. What plan do you propose?

Would you think it is a good idea to propose that you get to keep ninety-four gold pieces for yourself, with the six remaining given to a few of the other pirates? In fact, you can propose just such a thing, and if you do it correctly, your plan will pass!

Before explaining why, let me tell you a little more about the pirates. I mentioned that the pirates are perfectly logical, and not only that, they have the common knowledge that they are all perfectly logical. In particular, in their reasoning they can rely on the fact that the other pirates are logical, and that the other pirates know that they are all logical and that they know that, and so on. Furthermore, it is common knowledge amongst the pirates that they all share the same pirate value system, with the following strictly ordered list of priorities.

Pirate value system:

Most importantly, stay alive.

Secondly, get gold, the more the better.

After this, cause the death of other pirates, if possible.

Finally, all other things being equal, arrange when possible that gold goes to senior pirates.

That is, at all costs, each pirate would prefer to avoid death, and if alive, to get as much gold as possible, but having achieved that, would prefer that as many other pirates die as possible (but not so much as to give up even one gold coin for additional deaths), and if all other things are equal, would prefer that whatever gold was not gotten for herself, that it goes as much as possible to the most senior pirates, for the pirates are, in their hearts, conservative people.

What plan do you propose as pirate ten? The pirates will naturally consider pirate ten's plan in light of the alternative, which will be the plan proposed by pirate nine, which will be compared with the plan of pirate eight and so on. Thus, it seems we should propagate our analysis from the bottom, working backwards from what happens with a very small number of pirates.

One pirate. If there is only one pirate, the captain, then he mounts the plank, and clearly he should propose "Pirate one gets all the gold," and he should vote in favor of this plan, and so pirate one gets all the gold, as anyone would have expected.

Two pirates. If there are exactly two pirates, then pirate two will mount the plank, and what will he propose? He needs a majority of the two pirates, which means he must get the captain to vote for his plan. But no matter what plan he proposes, even if it is that all the gold should go to the captain, the captain will vote against the plan, since if pirate two is killed, then the captain will get all the gold anyway, and because of pirate value 3, he would prefer that pirate two is killed off. So pirate two's plan will not be approved by the captain, and so regrettably, pirate two will walk the plank.

Three pirates. If there are three pirates, then what will pirate three propose? Well, he needs only two votes, and one of them will be his own. So he must convince either pirate one or pirate two to vote for his plan. But actually, pirate two will have a strong incentive to vote for the plan, since otherwise pirate two will be in the situation of the two-pirate case, which ended with pirate two's death. So pirate three can count on pirate two's vote regardless of the plan details, and so pirate three will propose: pirate three gets all the gold! This will be approved by both pirate two and pirate three, a majority, and so with three pirates, pirate three gets all the gold.

Four pirates. Pirate four needs to have three votes, so he needs to get two of the others to vote for his plan. He notices that if he is to die, then pirates one and two will get no gold, and so he realizes that if he offers them each one gold coin, they will prefer that, because of the pirate value system. So pirate four will propose to give one gold coin each to pirates one and two, and ninety-eight gold coins to himself. This plan will pass with the votes of one, two and four.

Five pirates. Pirate five needs three votes, including his own. He can effectively buy the vote of pirate three with one gold coin, since pirate three will otherwise get nothing in the case of four pirates. And he needs one additional vote, that of pirate one or two, which he can get by offering two gold coins. Because of pirate value 4, he would prefer that the coins go to the highest ranking pirate, so he offers the plan: two coins to pirate one, nothing to pirate two, one coin to pirate three, nothing to pirate four and ninety-seven coins to himself. This plan will pass with the votes of pirates one, three and five.

Six pirates. Pirate six needs four votes, and he can buy the votes of pirates two and four with one gold coin each, and then two gold coins to pirate three, which is cheaper than the alternatives. So he proposes: one coin each to two and four, two coins to three and ninety-six coins for himself, and this passes with the votes of two, three, four, and six.

Seven pirates. Pirate seven needs four votes, and he can buy the votes of pirates one and five with only one coin each, since they get nothing in the six-pirate case. By offering two coins to pirate two, he can also get another vote (and he prefers to give the extra gold to pirate two than to other pirates in light of the pirate values).

Eight pirates. Pirate eight needs five votes, and he can buy the votes of pirates three, four and six with one coin each, and ensure another vote by giving two coins to pirate one, keeping the other ninety-five coins for himself. With his own vote, this plan will pass.

Nine pirates. Pirate nine needs five votes, and he can buy the votes of pirates two, five and seven with one coin each, with two coins to pirate three and his own vote, the plan will pass.

Ten pirates. In light of the division that we know will be offered by pirate nine, we can now see that pirate ten can ensure six votes by proposing to give one coin each to pirates one, four, six and eight, two coins to pirate two, and the remaining ninety-four coins for himself. This plan will pass with those pirates voting in favor (and himself), because they each get more gold this way than they would under the plan of pirate nine.

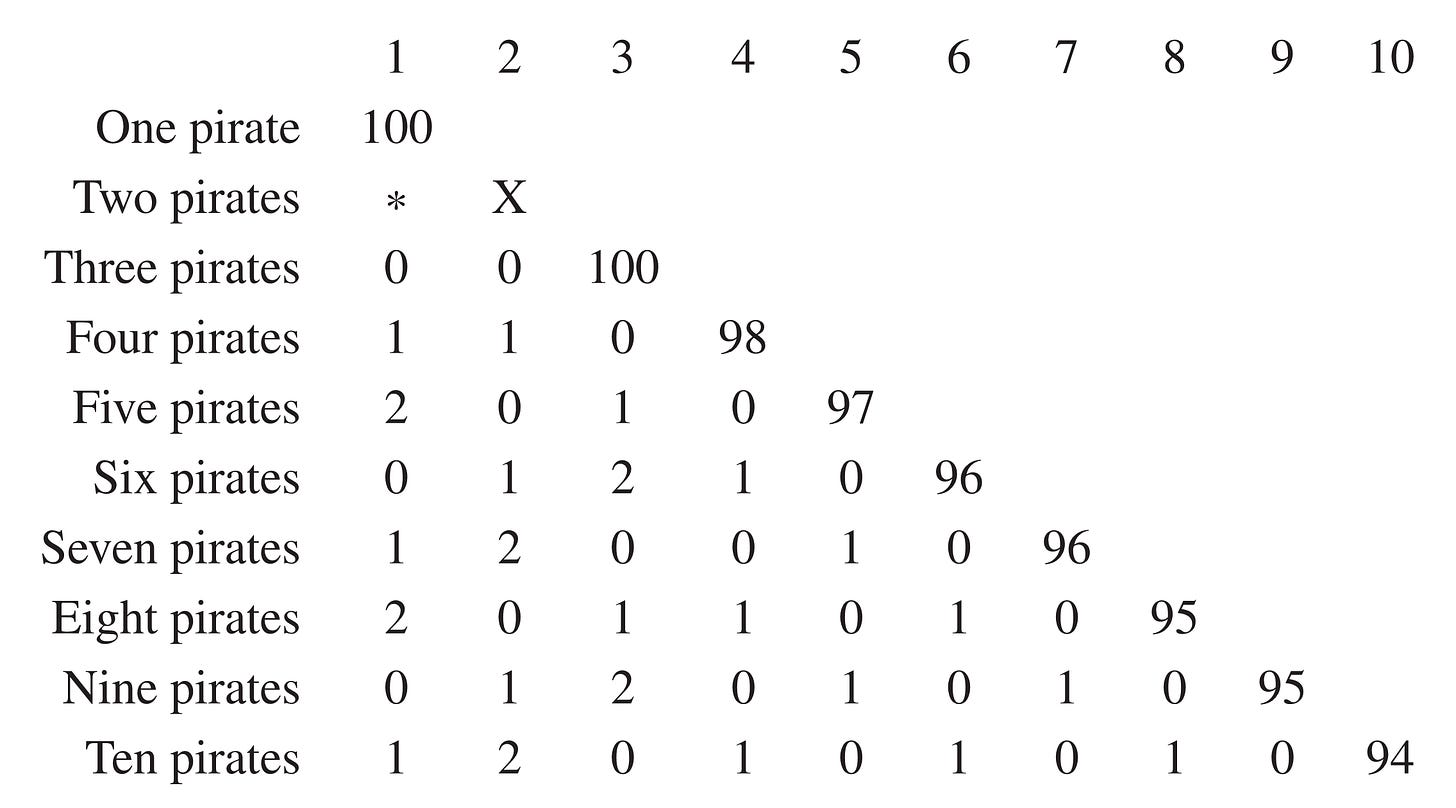

Let me summarize the proposals in the following table, where the nth row corresponds to the proposal of pirate n.

There are a few things to notice, which we can use to deduce how the pattern will continue. Notice that in each row beyond the third row, the number of pirates that get no coins is almost half (the largest integer strictly less than half), exactly one pirate gets two coins, and the remainder get one coin, except for the proposer himself, who gets all the rest.

This pattern is sustainable for as long as there is enough gold to implement it, because each pirate can effectively buy the votes of the pirates getting 0 under the alternative plan with one fewer pirate, and this will be at most one less than half of the previous number; then, he can buy one more vote by giving two coins to one of the pirates who got only one coin in the alternative plan; and with his own vote this will be half plus one, which is a majority.

We can furthermore observe that by the pirate value system, the two coins will always go to either pirate 1, 2 or 3, since one of these will always be the top-ranked pirate having one coin on the previous round. They each cycle with the pattern of 0 coins, one coin, two coins in the various proposals.

At least until the gold becomes limited, all the other pirates from pirate 4 onwards will alternate between zero coins and one coin with each subsequent proposal, and pirate n - 1 will always get zero from pirate n.

For this reason, we can see that the pattern continues upward until at least pirate 199, whose proposal will follow the pattern:

Pirate 199: 1 2 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 … 1 0 1 0 0

It is with pirate 199, specifically, that for the first time it takes all one hundred coins to buy the other votes, since he must give ninety-eight pirates one coin each, and two coins to pirate 2 in order to have one hundred votes altogether, including his own, leaving no coins left over for himself.

For this reason, pirate 200 will have a successful proposal, since he no longer needs to spend two coins for one vote, as the proposal of pirate 199 has one hundred pirates getting zero. So pirate 200 can get 100 votes by proposing one coin to everyone who would get zero from 199, plus his own vote, for a majority of 101 votes.

200 pirates: 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 … 0 1 0 1 1 0

Pirate 201 also needs 101 votes, which he can get by giving all the zeros of the 200 case one coin each, plus his own vote. The unfortunate pirate 202, however, needs 102 votes, and this will not be possible, since he has only 100 coins, and so pirate 202 will die. The interesting thing to notice next is that pirate 203 will therefore be able to count on the vote of pirate 202 without paying any gold for it, and so since he needs only 100 additional votes (after his own vote and pirate 202's vote), he will be able to buy 100 votes for one coin each. Pirate 204 will again be one coin short, and so he will die. Although pirate 205 will be able to count on that one additional free vote, this will be insufficient to gain a passing proposal, because he will be able to buy one hundred votes with the coins, plus his own vote and the free vote of pirate 204, making 102 votes altogether, which is not a majority. Similarly, pirate 206 will fall short, because even with his vote and the free votes of 204 and 205, he will be able to get at most 103 votes, which is not a majority. Thus, pirate 207 will be able to count on the votes of pirates 204, 205, and 206, which with his own vote and 100 more votes gotten by giving one coin each to the pirates who would otherwise get nothing, he can obtain 104 votes, which is a majority. The reader will investigate further in the questions. It is a fun problem to work out. The emerging phenomenon is longer and longer sequences of pirates in a row finding themselves unable to make a winning proposal, and then suddenly a pirate survives by counting on their votes.

Pirate treasure division with very few coins

It is also very interesting also to work out what happens when there is a very small number of coins. For example, if there is only one gold coin, then already pirate four is unable to make a passing proposal, since he can buy only one other vote, and with his own this will make only two votes, falling short of a majority. With only one coin, pirate five will survive by buying a vote from pirate one and counting on the vote of pirate four and his own vote, for a majority. The reader will investigate further in the questions.

Even the case of zero coins is interesting to think about. In this case, there is no gold to distribute, and so the voting is really just about whether the pirate should walk the plank or not. If only one pirate, he will live. Pirate two will die, since pirate one will vote against. But for that reason, pirate two will vote in favor of pirate three, who will live.

The pattern that emerges is:

lives, dies, lives, dies, dies, dies, lives, dies, dies, dies, dies, dies, dies, dies, lives, ....

After each successful proposal, for which the pirates live, there must subsequently be many deaths in a row in order for the proposal to count on enough votes. After each lives in the pattern, one must double the length with many dies in a row, before there is sufficient support for the next pirate to live.

One could recast this version of the process as the Popularity Game, played by high-schoolers trying to get into the In group. The lowest-ranked student stands before the others and is voted upon, whether they should be cast out or kept as part of the in group.

The philosopher's ruling council

In the ancient land of Philosophia there is a ruling council of philosophers, linearly ranked by power and prestige, with various accompanying benefits accruing in the order of this rank. Philosopher 1 is the recognized philosopher king, the most powerful, and then philosopher 2 and so on.

It is time to pick a new council, and according to the long agreed-upon procedure, the lowest-ranked philosopher proposes a new council and ranking. The newly proposed council can in principle include any citizen at all from Philosophia—candidates are not limited to the current council members, although strangely, it usually happens that the new council is constituted by previous council members. Given the new proposal, the council votes. If a majority approve, then this is the new council and ranking; otherwise, the lowest-ranked philosopher is kicked off the council and the next lowest-ranked philosopher makes a proposal. This process continues until a new council and ranking is approved.

I have described the members of the ruling council as philosophers, but let me say a little more about their values and the criteria by which they will be judging the proposals. The fact of the matter is that this is a power-hungry Machiavellian crowd, all desperate to be the philosopher king. Each council member prefers being on the new council above all other things, and will never vote in favor of a council that they are not on. Secondly, being on the proposed council, they would prefer to have as high a rank as possible (that is, a low number—being philosopher 1 is the best, 2 is second best, and so forth). Third, given that they will be on the council with a certain rank, they prefer that the council is as small as possible, so as not to have to share power unnecessarily.

Suppose that the council currently has five members. What will be the proposal of the lowest-ranked philosopher, philosopher 5?

Interlude

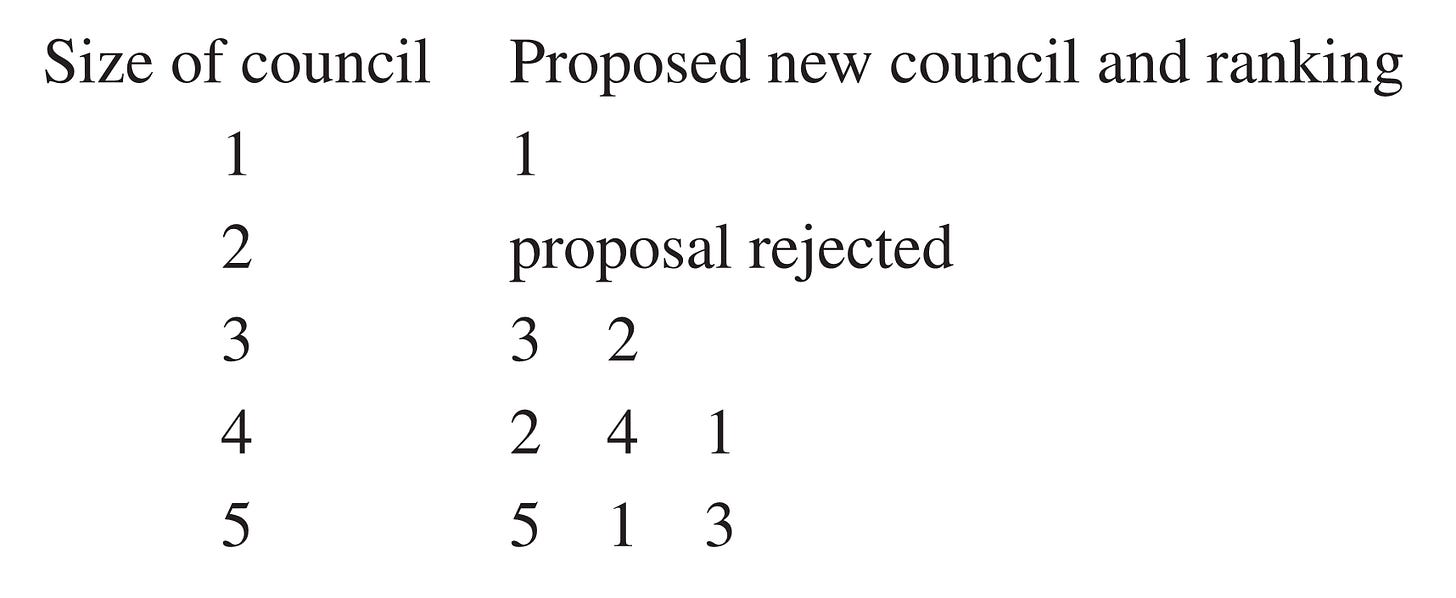

Let us solve the puzzle by working backward as with the pirate-treasure division. In order to know what philosopher 5 will propose, we seem to need to know already what philosopher 4 will propose, since that will be the alternative if we vote philosopher 5's proposal down.

So let us start with the easiest case, where the council has only one philosopher, the king. In this case, he will be the lowest ranked philosopher, and he can propose that the new ruling council is the same as the old ruling council, having only himself as a member. This is clearly the most desired situation, according to the philosopher values we mentioned, and so he will vote in favor and the plan will be adopted.

If there are two philosophers currently on the council, then philosopher 2 must propose a plan that will pass unanimously, since that is the only way to have a majority of two. But philosopher 1 will not approve of any plan except the plan of him being on the council alone, since that is what he can attain if philosopher 2's plan is rejected. And we said that philosopher 2 will only vote to approve a plan in which she is on the council. So philosopher 2's proposal, whatever it is, will be rejected and we will end up eventually with the council of just philosopher 1.

If there are three philosophers on the council, then philosopher 3, needing two votes, will propose a council of two, consisting of himself as king and philosopher 2 as the next member. This will be approved by philosophers 2 and 3, since they both prefer it to the result of the two-philosopher case. And furthermore, this is the best possible arrangement for philosopher 3, since he is made king on a council of size two.

If there are four philosophers currently, then philosopher 4 needs three votes. She will not get the vote of philosopher 3, who would be very well off if her plan were to be rejected, but she can get approval for a three-member council consisting of philosopher 2, herself, and philosopher 1, in that order. Each of these three will vote to approve, since they are better off with this than the alternative, and this is furthermore the best possible for philosopher 4, because she needs a three-member council, but must make philosopher 2 better off, and so philosopher 2 must become king (or should we say queen), and then philosopher 4 next, which is optimal, and then philosopher 1 will be third, which is better than he would get under the competing proposal of philosopher 3.

Consider now the case of five philosophers on the council. Philosopher 5 needs three votes and therefore will propose a council of size three, and indeed he can propose the council: himself, philosopher 1, philosopher 3, in that order. Philosopher 5 likes this very well, becoming king, and philosopher 1 prefers this to the preceding philosopher 4 plan, since he will have rank two instead of rank three. Philosopher 3 also likes this plan, since he wasn't on philosopher 4's proposed council at all.

Let us summarize the proposals as follows:

The reader will consider larger councils in the questions for further thought.

The color-matching game show

Suppose that you are a contestant on a game show, known for its perfectly logical participants. You and another contestant aim to coordinate your actions so as to win the big prize. Specifically, you want to cooperate so as to announce the same color at the same time.

You and the other contestant are led separately to your private rooms, each equipped with a desk and some messaging equipment. The game will proceed in rounds of simultaneous action. On each round, each of you privately chooses either to end the game and officially announce your color or to send a message to the other contestant. The message can be essentially as long as you like, provided you could type it in a reasonable time. The contestants are separated from each other and neither will know during a round what kind of action the other player will make on that round until after it has occurred. Messages are received just afterward. Each contestant has only one opportunity to end the game and announce a color—make sure to get it right!

If on a given round both contestants end the game and announce exactly the same color, then both win the big prize; but if the colors are different or if only one player opts to end the game and announce a color that round, then both have lost and the game is over.

Round 1 will begin soon. What will you do?

To get into the right mindset, we might increase the stakes by imagining that it is a matter of life and death—perhaps the two contestants are astronauts stranded in different parts of the rocket, and they must fire their rockets at exactly the same time in the same direction or they will die. They need to coordinate that action. The point is that I want to consider the game show situation under the assumption that both players want desperately to coordinate their action.

A fundamental problem of symmetry

It seems clear that neither player should end the game with a color on the first round, since there might be too little basis to expect that the other player will do so with the same color. Rather, the players should use the messaging capability to make a joint plan.

Suppose that you send a message proposing simply,

Let's say Red next round.

If the other player responding with the same message, then indeed you might win on round 2 this way. But suppose they don't? Are you still going to say Red next round? That would seem risky, and indeed, the ambiguity of this situation makes your message unwise.

To address that, perhaps it would be wiser to send a message like,

I'm going to say Red next time, if you tell me that you will, and otherwise I'll say whatever you say.

That might work. But suppose the simultaneous incoming message was,

I'm going to say Blue next time, if you tell me you will, and otherwise I'll say whatever you say.

What to do then? This would be a very dangerous situation, if each person takes their own message seriously, since if they followed through with the plan they would say Blue/Red mismatched.

This is actually a quite general logical problem with the puzzle, and many proposals face a problem when the partner contestant makes exactly the same message, but with a different color. It can be interesting/difficult to see at first how to resolve this issue.

For example, saying

Let's say Red on round 5, if you confirm by then

might seem to get around the trouble, but ultimately this has the same kind of problem, if the other player says the same thing but uses a different color. If one player tries to defer to the other, then perhaps the other defers at just same time, preventing the deferral from succeeding.

Perhaps one tries to win the game by establishing leader and follower roles for the player—one player might be adament and insist that their own plan is the one to be followed, or they might be deferential and insist that the other player should specify the color and round on which to win. The problem arises when two stubborn players both insist on being leader or two deferential players both insist on the other deciding. What to do then?

This fundamental symmetry between the players almost turns into a proof that there can be no deterministic solution of the puzzle, since if both players play optimally, the other player might be led by similar reasoning to play an exactly isomorphic strategy, but perhaps with the colors permuted (since there could be no reason to prefer one particular color over another). If this is right, all messages will be identical, except possibly with different colors, and this would prevent a win.

Breaking the symmetry

Meanwhile, there are a variety of ways to try to break the symmetry and somehow distinguish one player from the other, causing in effect leader/follower roles, which will enable a color-selection solution.

For example, perhaps it is promising to say,

Let's say Red on round 57, unless you've made a proposal for a later round, in which case we'll do that.

If the numbers are large enough, it seems unlikely that both players will be picking the same number, and so this strategy will break the symmetry and they can come to agreement.

One might also try to break the symmetry by using other information about the players, e.g. alphabetical order of their names, their ages, etc. Any asymmetry in the players could in principle be a reason to settle on one player's choice rather than the other and thereby come to agreement. But actually the enormous range of ways to break the symmetry is itself a problem, since how can the players settle on just one of them? If we have different plans on how to break the symmetry, then we need to break the symmetry first in order to decide how to break the symmetry.

Randomness

There are other ways to introduce randomness explicitly. One promising way to proceed is to say on the first message,

I'm going to say Red on the next round, if you also say you will; but if you mention some other color, then (for the first color you mention) I'm going to flip a coin each time between Red and that color to determine which one I'll tell you I'm going to say, until we happen to both propose to say the same color for the subsequent round. And then we shall win.

This randomness approach gets around the symmetry obstacle, since if both players adopt this approach, then it is likely that their colors will match on some round and then they will win on the next. In effect, the coin flips allows each player randomly to choose the leader or follower role, and so it is likely that they will be compatible at some point.

Computer communication protocols often face similar such coordination problems, where the two machines need to establish a priority between them, but it doesn't matter which is which. Many protocols adopt randomness methods in order to make these decisions.

Schelling point

Thomas Schelling realized that many coordination problems can be solved even in the absence of communication. For example, suppose two people aim to meet on a certain day in New York City, but no plans have been set other than the specific day and they have no means to contact or communicate with one another. Where and when should they meet?

It turns out that many people, when asked this question, propose the solution: meet at noon at the information desk in Grand Central Terminal. Why there? Because Grand Central is a very common well known meeting point in the city—it is famous for meeting; it is a beautiful grand place in which to wait; it is easy to get to from nearly anywhere in the city by many different modes of transportation; and it is convenient for many further prospective destinations. Why at the information booth? Well, if we are meeting in Grand Central, then the information booth in the very center of the grand hall seems the most natural choice. Why noon? Well, if we have to pick a canonical meeting time that would occur to both people, the very middle of the day seems natural. This kind of solution is known as a Schelling point.

Is there a Schelling point for where to meet in your city? On your university campus? Is there a Schelling point for the opening move in a chess game? Is there a Schelling point for which play to rehearse for the urgent surprise performance tonight?

And is there a Schelling point for the game show color coordination game? Yes, indeed there is. At Oxford we had used this game for part of the admissions interview discussions we held for candidates seeking entry to the program in philosophy. More than 90% of the candidates had used Red as their color in the discussion in their initial messages—their proposed messages all involved Red more than any other color. This is clearly a Schelling point color, and so one would do well in the game to propose Red; agreement will become much more likely.

Fitch's paradox

How does knowledge relate to truth? Let us try to articulate some basic principles. Many philosophers, for example, take it as part of what it means to have knowledge that one can only know things that are true. That is, if you know a proposition p, then (among other things) it must be the case that p is true. You might happen to believe some untrue propositions, indeed, you might have very strong grounds for your belief—you might have what seems irrefutable proof—but if the proposition isn't actually true then you cannot correctly be said to have knowledge. Let us express this principle with the following principle:

Every known statement is true.

Secondly, a sort of weak converse of this might also seem reasonable. Namely, that every true statement is in principle something that could be known.

Every true statement is knowable—it is possible that we could know it.

Frederic Fitch (1963) makes a startling conclusion on the basis of these two assumptions, plus other ordinary assumptions, such as knowing the conjunction of A and B entails knowing A and knowing B separately. Fitch argues for the following conclusion:

Therefore, every true statement is already known.

Let us give the argument. Suppose toward contradiction that there were a true statement φ that we do not know. So it is true that "φ and we don't know φ." So by (2) it is possible to know "φ and we do not know φ." Thus, we would know φ and we would know that we do not know φ. But that is impossible, since if we know that we do not know φ, then by (1) it would have to be the case that we do not know φ, contrary to the first clause. So there cannot be any true statement that we do not know, establishing (3).

Is it right?

Cheryl's rational gifts

Let me conclude the chapter with a final puzzle with which I shall leave you. Around the time that the Cheryl's birthday puzzle was going viral, I felt that the mathematical community deserved a more difficult and interesting transfinite version of the problem. So I created Cheryl's rational gifts, as follows.

Cheryl Welcome, Albert and Bernard, to my birthday party, and I thank you for your gifts. To return the favor, as you entered my party, I privately made known to each of you a rational number of the form

\(n-\frac{1}{2^k}-\frac{1}{2^{k+r}},\)where n and k are positive integers and r is a non-negative integer; please consider it my gift to each of you. Your numbers are different from each other, and you have received no other information about these numbers or anyone's knowledge about them beyond what I am now telling you. Let me ask, who of you has the larger number?

Albert I don't know.

Bernard Neither do I.

Albert Indeed, I still do not know.

Bernard And still neither do I.

Cheryl Well, it is no use to continue that way! I can tell you that no matter how long you continue that back-and-forth, you shall not come to know who has the larger number.

Albert What interesting new information! But alas, I still do not know whose number is larger.

Bernard And still also I do not know.

Albert I continue not to know.

Bernard I regret that I also do not know.

Cheryl Let me say once again that no matter how long you continue truthfully to tell each other in succession that you do not yet know, you will not know who has the larger number.

Albert Well, thank you very much for saving us from that tiresome trouble! But unfortunately, I still do not know who has the larger number.

Bernard And also I remain in ignorance. However shall we come to know?

Cheryl Well, in fact, no matter how long we three continue from now in the pattern we have followed so far—namely, the pattern in which you two state back-and-forth that still you do not yet know whose number is larger and then I tell you yet again that no further amount of that back-and-forth will enable you to know—then still after as much repetition of that pattern as we can stand, you will not know whose number is larger! Furthermore, I could make that same statement a second time, even after now that I have said it to you once, and it would still be true. And a third and fourth as well! Indeed, I could make that same pronouncement a hundred times altogether in succession (counting my first time as amongst the one hundred), and it would be true every time. And furthermore, even after my having said it altogether one hundred times in succession, you would still not know who has the larger number!

Albert Such powerful new information! But I am very sorry to say that still I do not know whose number is larger.

Bernard And also I do not know.

Albert But wait! It suddenly comes upon me after Bernard's last remark, that finally I know who has the larger number!

Bernard Really? In that case, then I also know, and what is more, I know both of our numbers!

Albert Well, now I also know them!

What numbers did Cheryl give Albert and Bernard in Cheryl's rational gifts?

This question will remain a cliff-hanger, as far as this book is concerned. If you solve it, then kindly send me an email with your solution to jdh@hamkins.org. I would love to hear about it!

Questions for Further Thought

Do Albert and Bernard really need full common knowledge of the fact that Albert knows the month (and not the day) and Bernard knows the day (and not the month)? What fragment of common knowledge do they need exactly?

Can you solve the hidden prize problems with Caroline and Susan, and with Roland and Christopher?

Consider these followup questions regarding the hidden prize puzzle with Sheila and Colin.

Did Sheila know initially that Colin did not know where the surprise was?

Did Colin know initially that Sheila did not know where the surprise was?

Did either of them expect the first silence?

In that case, what affect on their knowledge did that silence serve? How did they learn anything from it?

Did Colin know that Sheila knew that Colin didn't know initially dwhere the surprise was?

Did either of them expect the second silence?

Suppose that the trusted visitor to the island of the blue-eyed islanders had instead announced, "At least a dozen of you have blue eyes." What would happen and when?

Suppose that instead of making a public announcement, the visitor to the island of the blue-eyed islanders had privately told each person, individually, that at least one person on the island had blue eyes. Would this fundamentally change the situation?

Suppose that the island has 63 inhabitants with blue eyes and 37 inhabitants with green eyes, and the trusted visitor announces "at least one of you has blue eyes and at least one of you has green eyes." If the custom to make the flashy exile display applies whenever an islander comes to know their own eye color, then what will happen and why?

Verify the pirate treasure analsysis in the text up to 200 pirates and more, and investigate how the pattern of pirate treasure division continues beyond, with very large numbers of pirates.

What are the successful pirate-treasure division proposals when there is only one gold coin? Two gold coins?

What is the outcome of the pirate-treasure division protocol when what is being distributed are debts rather than coins? Assume that each pirate wants to live, wants to avoid debt, and so on.

What is your analysis of the Popularity Game for high schoolers trying to get into the In group?

Analyze the philosopher's ruling council proposals for larger councils. Is there a unique determinate answer when there are six philosophers? If not, does this affect how judgements might be made for seven or more philosophers? Can we find reasonable value systems for which the proposals will become determinate?

What is your assessment of the argument in Fitch's paradox? Do you accept the premises of the argument? Do you accept the conclusion?

A group of children has just come into the house after having played outside, and it happens that each of them has some mud on their forehead. Each child can see the mud on the other children, but doesn't know whether their own forehead is muddy. The mother remarks, "at least one of you has mud on your forehead." Then, she says, "raise your hand if at this moment you know that you have mud on your forehead," and she repeats this instruction over and over. What happens?

You and two of your friends are shown five hats—two blue and three red—and then you are blindfolded and each of you get one of the hats placed on your heads (the two extra hats are removed). You are each to deduce the color of your own hat. Your first friend removes his blindfold, observes your hats and says that he cannot deduce the color of his hat, and he leaves, taking his hat with him. Your second friend removes her blindfold, looks at your hat, and also says that she cannot deduce the color of her hat. Without removing your blindfold, can you deduce what is the color of your hat?

You and two friends are placed in circle, and each of you is given either a red or a blue hat. You are told to raise your hand if you see a red hat, and that whoever can deduce their own hat color first will receive a prize. At the start, all three of you raise your hands, and then stand in awkward silence for a few minutes. Eventually, your friend says, “Red!.” She was right, but how did she know?

Further reading

Vanderschraaf, Peter, and Giacomo Sillari. 2022. Common Knowledge, Fall 2022 edn. In The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, eds. Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. An excellent philosophical account of common knowledge.

Credits

The two-generals problem is a classic of the subject. The history of the Cheryl's birthday puzzle can be found on Wikipedia. I had created the hidden surprise logic puzzles and the color coordination game show puzzle to use in admissions interviews for PPE at University College Oxford; they have subsequently appeared in The Guardian and on YouTube as I had mentioned. The pirate-treasure division problem appears to have been around for some time, and I am unsure of the exact provenance. Ian Stewart wrote a popular 1998 article for Scientific American analyzing the patterns that arise when the number of pirates is large in comparison with the number of gold pieces. Many versions of the puzzle, such as that on the Pirate Game entry on Wikipedia, are slightly different than mine. For example, many authors have that tie-votes count as success, and for this reason, the outcomes are different. I prefer the strict-majority variation, since I find it interesting that one must sometimes use two gold coins to gain the majority, and also because the death of pirate two arrives right away in an interesting way, rather than having to wait for 200 or more pirates as with the plurality version. Another (inessential) difference is that some authors have the captain on the plank first, and then always the highest-ranking pirate making the proposal, rather than the lowest-ranking pirate, with the pirate values similarly swapped to prefer the lowest-ranking. This corresponds simply to inverting the ranking, and so it doesn't fundamentally change the results. The pirate image is Buried Treasure, by Howard Pyle (Public domain), obtained via Wikimedia Commons. My puzzle, Cheryl's rational gifts, appeared on my blog, and was inspired by a suggestion of Timothy Gowers to find transfinite versions of the Cheryl's birthday puzzle. The illustrations of the Logic Bar, the two generals, the crocodile, and the blue-eyed islander were created by the author via DALL·E and are available in the collection at https://labs.openai.com/sc/QJC44RJTdvvy6dLDk62dTYLt.

Re: the two generals, its applicability is limited to the very specific positive confirmation contained in the communication, right? For example, consider the following message:

Confirm attack at dawn, and please respond if you agree. If I receive your confirmation, I will not respond, so take my silence as final agreement on the plan. In any other scenario, I will not assume agreement, and send a message to resume the discussion.”

If the second general sends confirmation, and receives no response, don’t both generals now have complete information? Or am I missing the point of the exercise.

Short story re: blue eyed islanders: https://slatestarcodex.com/2015/10/15/it-was-you-who-made-my-blue-eyes-blue/